Last week, Julia Moore of The Center for Implementation had the pleasure to talk about our systems to work more effectively through academic publications. Below you can find the slides, the recording, the transcript, and some extra goodies and commentary.

The recording

The Transcript

We edited this transcript for clarity and ease of reading.

Okay, everyone. So welcome. Thank you so much for joining us. Good morning. Good evening. Good afternoon.

My name is Jonathan Scaccia, and yes, we’ll ensure that both the slides and the recording will be out afterward so that you can go back and reference and share them with your friends. So we have a tight 30-minute agenda today because we wanted to maximize the value that you can get out of spending your time with Julia and me today. So let’s get right to it.

Within the time we’re spending today, we’ll help you develop and have a system to read and understand scientific articles better. We’ve been working in this field for a while, and we have our introductions on the next slide, but one of the barriers we’ve run into, again and again, is that it can be super challenging to engage with the primary scientific literature.

Part of that is access. But it’s also a strange type of writing. These things are arranged in ways that don’t immediately grab people. So we have systems that we’ve been developing in parallel to help you understand the scientific articles better, but also a system to keep up reading that has helped Julia become one of the foremost experts in implementation science. And then we also have tools that will help you continue to stay up to date going forward along with some other, along with some other benefits that we’ll talk about. So Julia, if you could give a one-minute spiel about who you are and what you have to offer everyone?

Thanks, Jonathan. So my name is Julia Moore. I’m the executive director at The Center For Implementation. It’s funny that you call this reading like a scientist because l call myself a rogue scientist; I live in a different space now. I am all about bridging the gap between the research that we all do and the practice that happens on the ground. And so how can we bridge those two together? And to do that, we have to deeply understand what does the science tell us about how best to implement it so that people can put that into action. And so that’s kind of what I do and what we do at The Center For Implementation

Thanks, Julia. And my name is Jon Scaccia. I’m a community psychologist and implementation scientist by training, and over the past 15 years now, I’ve been interested in how we get good ideas into practice. And one of these barriers to getting these good ideas out there happens way, way back at the beginning in how people identify and consume scientific literature. So through my work doing community-based evaluation and thinking about where there might be technological solutions to a lot of these problems, we developed a web-based application called PubTrawlr that is designed to help people get the key messages and stay up to date in a much more effective and efficient way.

Where we want to go by the end of our time together is: What if we could actually make science, these public goods, these things that are funded through our resources, these things that are designed to benefit huge numbers of people—what if we could better access and use this knowledge? There’s this idea of the 17-year implementation gap? What, if we could get rid of that? What would be the things that you would have access to mentally and more importantly, what could you do? How could you take this information and apply it within your settings?

So I’m going to be talking about how to sort of unpack a scientific article. And then Julia will talk about her system for sustaining that work. So where we always want to start is the abstract. And oftentimes this is one of the only things that you’ll be able to access if things are paywalled and that’s a whole other kettle of fish we could talk about.

Five things that should be in every scientific abstract

So five things should be in every scientific abstract. And when you approach one, you should try and look for these five things because that give you the key message and tell you whether or not you should continue to try and explore this article.

So the first is the context; what is the background of the study? So this tells you hopefully in a sentence or two, like what’s the underlying need for this article? Is this something that has not been addressed before? Is this something that tries to build upon previous research? Why does this article exist at all? This is the context, and we want to find that right away.

We then look for the questions. Every good paper has a good question. So what are the authors trying to discover? What are they trying to answer? How are they trying to push science just a couple of steps forward? Even opinion pieces and commentaries are pretty common in journals like Health Affairs or The Annual Review of Public Health; they have a question that they are trying to answer that will help give us more information than when we started with.

We then want to look for the methods. So how did people go about answering that question? Really, this is the most technical part of any article, but it’s also really important that we understand how people tried to answer the question.

This is what I love about scientific research. There are innumerable ways to answer questions. That’s what makes it fun. It makes the inquiry and the exploration process of this work so invigorating, at least for me. So I geek out on methods. So while there are many different ways that you could be answering the specific question in this abstract, you want to try and understand how these authors and this particular team chose to answer.

The next thing we want to find is the results section. This is what the people found. It may be in the form of some statistics. It may be a sentence like “we found that this obesity prevention program lowered BMI by five points across groups.” This is where we find what happened, but it doesn’t end there.

The last thing we should be looking for is the implications. So what did this study mean? So what’s the author’s commentary on the overall importance of these results? What are the consequences? What does it suggest people need to do next? Because science is an ongoing process. So we start with this with a need. And then we end with, “okay, now that we know this, and we found the way to know this, where do we go next?”

Example

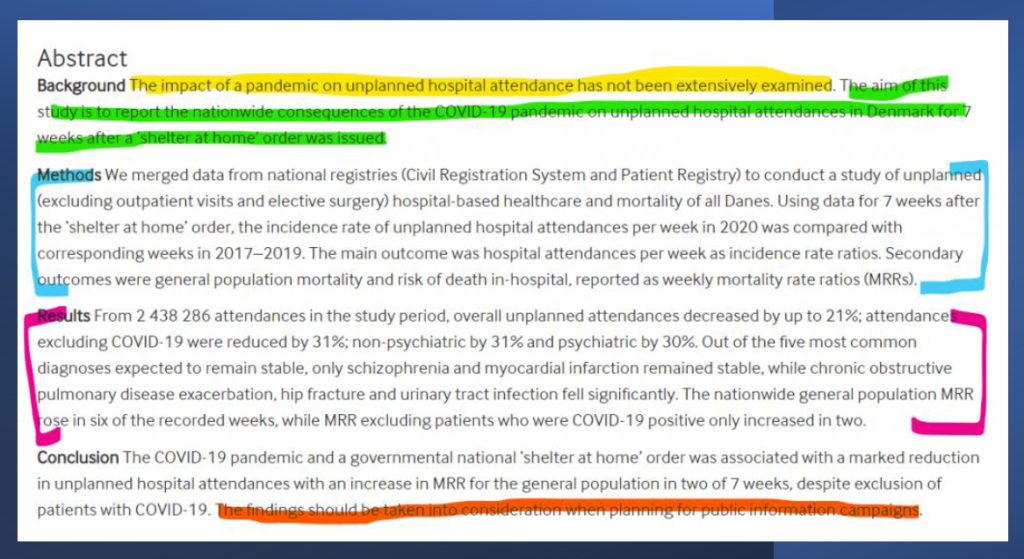

So here is an abstract that I just pulled from some somewhat at random where I wanted to see if I could identify these five elements. So in yellow, we have the impact of a pandemic on unplanned hospitalization. Attendance has not been extensively DISA examined. So there’s your context. That’s the reason this article exists? They had not, to the author’s knowledge, studied unplanned hospital attendance under a pandemic.

So what’s the question? In green, they aim to find the national consequences of COVID on unplanned hospital attendance for the six weeks that the shelter that the shelter-at-home order was issued. So the question is, did COVID impact unplanned hospital attendance under the methods here?

We see how these authors chose to answer this question. So they looked at a couple of data sets (in blue). They compared them using the outcome of hospital attendance and secondary outcomes of and risk of death. Okay. So that’s what they did. They took these two data sets, walked them together, and saw whether or not the pandemic had any impact on hospital attendance.

So what did they find? What were their results (in purple) This is the fourth thing we looked for. So from this period, they found unplanned attendances decreased non-COVID hospitalizations decreased, non-psychiatric ones decreased, and psychiatric ones decreased. So not many unplanned hospital attendances during the pandemic. These went down. Okay. That’s, that’s pretty interesting.

What does that mean? So we can get that from the conclusion, and I’ve highlighted this in this Auburn color here. These findings should be taken into account when planning for public information campaigns. So if we know that during pandemics, unplanned hospital admissions go down, what does that tell us about how we communicate to people about how they should access health services? How does that help us to understand what people should do in pandemics?

Maybe there’s fear of going to hospitals? We don’t know that yet. This is what would happen next, but we know from what’s outlined here, why they did this study, what they looked at, how they looked at it, what they found and why or what they plan to do next.

So really what we do is we try to find out what the question was, how did they go about it and what are they trying to answer? And something that Julia is really going to home next is that reading a scientific article is not like reading a novel. You’re not picking it up, wondering what’s going to happen next. Some people choose just to read the introduction and the conclusions. Some people choose to read the abstract, the methods, and the results section. So they get the sense of what’s going on, how they did it, and what they found.

I want to emphasize that there are no spoilers in scientific articles, so you don’t have to worry about being surprised while reading them. Ideally, you want to get a sense of the whole thing before you proceed. And now Julia is going to talk about the system that she developed that helps us to engage with different parts of an article to expand the total number of things that we can consume.

Getting through articles at scale

Awesome. Thanks, Jonathan. So okay. So I think the important context to know is the way I’m reading an article is based on the role that I have kind of in the system. And that is that I need to know a lot of information about what the literature tells us about how to implement things. So I need to consume a huge amount of different pieces of information, but I’m using that for one very specific purpose to make that information really practical and accessible and guide how people are implementing changes.

So, several years ago, I realized that one of the most important things I need to do in my job is to keep up to date on the literature. And it sounds easy, but it’s very hard. And so I developed, it took me months, but I developed this system that helped me ultimately read over 300 articles over the span of about two years.

Whenever I get an article, I email myself the article, and an email to myself.

Then what I do is I snooze articles so that it is the very first thing that shows up in my inbox every morning. So I start working really early. I like to put them in for 6:00 AM so that I know that is the first thing in my inbox. So it is snoozed and designed. So I’m going to get a new article every morning at 6:00 AM in my inbox. If you start at like nine, maybe adjust the time.

I know that I have to read the article at the beginning of the day, for sure, in the first 30 minutes of the day. And if I do not read my article in the first 30 minutes of the day, I know I will not get to it. I scheduled it for a different day, and I have to just like move on. Cause I know it’s not going to happen if it doesn’t happen right away.

And then this is where I do something that I can’t believe I shared at the beginning that I do this. Cause it feels sort of wrong, but it helped me really get through a lot of articles and like get to a place where I understood what was happening in the literature in my field. So I start by skimming the abstract and by skimming, I mean less than 30 seconds, like it might be 20 seconds, that it takes me to skim through this abstract. And sometimes, honestly, half the time, the article’s not actually that relevant or helpful to what it is that I’m doing.

So like a perfect example, someone might have developed a new tool, like an assessment tool for something, but it’s content-specific to a topic area that I don’t work in. So it’s good to know it’s out there, but I don’t really need to read the article if that happens. I literally, cause I had this email in my inbox with a link to this article.

I reply to the email I sent myself and I copy and paste the abstract that way. I know that if I want to search within my own inbox, I can actually find that article again, but I don’t actually read it. And now all of a sudden the process of reading my article that morning took like one and a half minutes, and I can move on with my day.

Assuming the article is relevant, which happens, give or take half the time, I read the full abstract. So remember I skimmed the abstract like 20 seconds and I’m like, “Ooh, actually this kind of is relevant.” So now I’m going to read it in more detail. I’m going to look at the sections and Jonathan just kind of set up like those, these very specific sections of the abstract. I’m going to figure out which ones I think are going to be most helpful for me given my role.

Interestingly, often the results and discussion matter a lot more to me than say, Jonathan talked a lot about methods, which he’s interested in. I want to know what’s the practical implication of the thing that they’re telling me about in this article. So I read, truly read that in that abstract.

And then I skim the intro. I don’t read full intros. I want to say a massive thank you to every author out there who has good topic sentences and or headings in their intros because it makes reading the intro so easy. Right? I read the first sentence of every paragraph and people who write beautifully and write concisely–you can just read that first sentence of every paragraph in the intro and get through it in like a minute.

But sometimes I might be like looking out for something specific. Currently, I’m doing a lot on sustainability planning. So if I’m reading articles and I see the word sustainability, I’m going to pause and read that in more detail. So I’m skimming through the whole thing all of a sudden, so I’ve gone through it. And I read all of these first lines.

What starts to happen is then something seems relevant. Now I need to do honestly the hardest part of this whole process, right? So like everything up to this point is like fast, easy HT. I’m like three minutes into reading my article. And now all of a sudden I’m like, “whoa, this actually is relevant.” I literally like move where I’m sitting. I try to take a deep breath because shifting your mindset from this, like skimming through articles to like deep reading is an entirely different process. So I take a deep breath, I pause, and I’m like, “Okay, now they’re telling me something that truly matters to what it is that I’m doing.” And I’m going to pause. I’m going to read it. I’m going to reread sentences. Sometimes I realize I kind of need to go up a few paragraphs and maybe figure out how they got to this place. So I might jump back and forth, but I make sure that I do like deep reading to make sure that I know what it is that they’re saying and how that is truly relevant to the work that I am doing.

Once I do that, I email myself a one-sentence takeaway from this article. So sometimes it’ll be things like,”Ooh, this is a great tool to help for sustainability planning.” Maybe it might say something like, “Ooh, interesting context framework. I would love to check this out when I’m looking for frameworks about this,” or, “Ooh, this article seems nicely aligned with…..”, and I’ll like mention another article. And so I like write myself a one-liner so that I can kind of remember things and I’ll even tell a secret….

…I sometimes write things like, “this was sort of a dumb article.” I didn’t really agree with what they had to say. Sometimes I’m like, I don’t need to read this again because I’m not sharing these one-liners with other people. They’re one-liners for me so that when I want to go back to those articles, I can go and look at them and figure out what I thought of the article.

Sometimes I also have an action item for myself. Like, “Make sure you incorporate this with something else.” Do you know what I mean? Or use this on X project or send this article to someone else. And then I always copy-paste the abstract below because this is the biggest way I find articles now. Say I’m looking for sustainability. I’ll just go into my articles folder, search the word sustainability, and then all the article abstracts pop up that have that word. And I find it really helpful. It honestly rarely takes me 15 minutes to get through an article, often more like seven or eight, because I’m not reading the whole thing I’m reading what matters most to me. So thanks, Jonathan. That’s my kind of quick summary of how I read a massive number of research articles.

The System to Stay Up to Date

The volume of what you’ve been able to put together, Julia, is super impressive. And it’s really been a benefit to me as I try to increase the fund of knowledge that I have. So as part of like the system to help you all stay up to date, we want to make sure that you have the tools that you, being the audience, not you, Julia, but you too, Julia. We want to ensure that you have the tools to follow up on this.

So when we’re, when we’re all done, we’ll be providing you these, these slides, and this recording. But I mentioned earlier that there are a bunch of other barriers that are preventing people from really engaging with the scientific literature. And this has become so much more urgent now in this age of misinformation where it’s very difficult for people to parse out what scientific findings mean.

How do we couch them and how do we use these to move forward? So as part of registering through this webinar, we also enrolled you in our Week in Science newsletter. This is something that goes out from PubTrawlr once a week that pulls from the top journals out there and says, “these are the most important articles or the most representative articles for the week. This is what they found, and this is what they mean.”

So we want to try and ease how you can stay up to date with the extremely prominent core stuff. So things from like Nature or Science or the New England Journal of Medicine, for example.

But we’re just a bunch of people trying to solve this problem. We could really benefit from your input into this. We really need people to be helping us to design more effective ways to help people consume science. So next week we’ll be setting up a referral program for the newsletter. So everyone who signed up would have a specific code. This is all automatic. And if you get people to sign up with your code number we have a series of escalating rewards. So, you know, pretty early on, this is like these cool PubTrawlr stickers. But later on, if you get a bunch of people, these are things like swag and, and more but what we’re really looking for is what type of information out there and potentially what more targeted information will help practitioners and academics and just the regular people in the field do their job more effectively.

And we think so strongly about this that we’re sponsoring a contest using these referral codes. So by Halloween, by October 31st, the people with the greatest number of referrals will receive $1,000 USD So if you get a bunch of people to sign up with your email code, and you’re our number one person, $1,000. Second prize is 500 USD, no strings attached. We just feel so strongly that we want everyone’s input into this process. So this is where we have these milestones along the way to help incentivize you spreading the word that, “Hey, we’ve got this cool project to try and get people more into science and more into the nuts and bolts of science.”

And we hope that these three tools, how I’ve deconstructed abstracts and the system I’ve used for that, the system that Julia has for just basically crunching through a huge number of articles with that practical lens. This is a system for staying up to date. It’s not a system for literature reviews, so to speak where you would have to be more in-depth, really try to understand and break down and parse out the methods which I like to do anyway. But that’s a different skill set.

And, and the reason behind all this, and I really want to sort of hammer this point home before we’re done. Science is a public good. These things that are being created and published, this is stuff that’s supposed to be for the benefit of all humankind. These are things that we can pick up and use to make life better health, wellness, well-being, whatever sort of our outcome of interest is, we can use this information to make things better for the people in our communities and our global community.

So the more information that we all have about how to do this more effectively and how to get through that implementation gap the more good we put into the world, and that’s super important for us. So I want to thank you all for coming today. Again, the slides and the recording will be available following this. But otherwise, I hope everyone has a wonderful day and thank you so much.

Two more things!

Sign up for our Week in Science Newsletter here at PubTrawlr!

And download the full slide set here!